|

Club de Patinaje LINCES

Medellín |

Number 1 Olympics, 1998 Special Issue

With Barry Publow

QUESTION

I want to use my K2 flight 76s for conditioning and strength

training. Is there a way to increase the spin friction on the

wheels to achieve a better workout at lower speeds? Or should

I get one of those mini-parachutes attached to a harness?

ANSWER

There are several ways to achieve gains in muscular strength

for speedskating. Off the skates, resistance training with

weights and plyometric training exercises can be used to

develop explosive strength and power in the skating-specific

muscles. However, what these auxiliary exercises lack is true

specificity (i.e., no matter how much you try, it is

impossible to exactly simulate the way the muscles function

and the way the joints move during actual skating). Therefore,

one must focus on more precise methods performed on skates.

There are several wavs to increase the level of workload while

at lower speeds:

LUBRICATE YOUR BEARINGS WITH THICK GREASE

PRO: This effectively increases the wheels rolling resistance,

necessitating more muscular effort.

CON: Doing this increases the bearings resistance so much that

gliding time is dramatically reduced. Although the physical

training effect is favorable, this disrupts ones accustomed

rhythm of push, glide, and recovery. The problem here is that

if used too often, you may find it diffcult to re-adapt once "fast"

bearings are back in your skates. You also will need 2 sets of

bearings because of the workload required to de-grease after

such a training session.

SKATE UPHILL

PRO: Skating uphill puts increased demands on the skating

muscles, particularly the extensors of the hip joint. The

results is increased leg strength.

CON: Once again, hill skating reduces the glide portion of the

stride. This training technique is great so long as it does

not constitute the primary training method. In addition, the

relative contribution of the leg muscles during steep uphill

skating is different than on flat terrain. However, hill

skating can and should be used in conjunction with other such

"muscle loading" training techniques.

SPECIAL EQUIPMENT: THE PARACHUTE

PRO: Runners have used mini-parachutes for years to increase

the resistance to forward motion. It does this job rather well,

requiring higher than normal efforts for any given speed.

CON: Parachutes provide resistive force in direct opposition

to forward motion in much the same way a hill does. Therefore,

the use of such a device can have the same negative

consequences.

THE FITNESS HARNESS:

PRO: Rather than providing resistance to forward motion, this

device provides direct resistance to the muscles themselves

using rubber tubing. Therefore, such a device avoids the

technique-altering pitfalls of hill skating or the use of a

parachute.

CON: Such harness devices can prove cumbersome to some, and

although they do a reasonable job, the resistance they provide

doesn't perfectly match the muscle's ability to generate force

over changing joint angles.

Late Spring 1998

With Barry Publow

QUESTION

"How do skaters handle speeds in excess of 40 mph, such as the

X-games? Every time I go down a large hill, once I hit about

40 mph my skates start to feel light as if my legs are not

putting as much downward force on the ground. How do the X-games

skaters maintain control when they exceed these speeds?"

ANSWER

As soon as we start talking about doing downhill at very high

speeds (e.g. 40 mph), there are a few things that have to be

considered:

Surface contact/traction

The "trueness" of the wheels and frame

Aerodynamics.

Surface Traction

Many of the skaters at the X-games spend a considerable amount

of time testing wheels and then selecting the ones which give

them the best combination of high traction and low rolling

resistance. Also, I understand that many skaters probably use

a new (or almost new) set for each run down the course. Even a

slightly worn set of wheels does not (usually) have the same

level of "grip" a new set does. According to Todd Gormick of

Hyper Wheels, most skaters prefer to use a new wheel which has

been skated on just enough to remove the "mohawk" (the thin

raised strip of urethane which runs along the middle of a new

wheel).

"Trueness"

At high speeds, even very slight misalignments in the shape of

the wheel and/or hub become magnified. This is largely

responsible for the much dreaded "speed wobble" which many

skaters encounter when approaching 40, or even 30 mph. A

slightly bent frame would also cause equally devastating

problems. Depending on the severity of the misalignment,

either of these two sources could cause one or more wheels to

have poor surface contact with the pavement. This would

seriously compromise the stability of the skater. Wheel

manufacturers do use some form of quality control to ensure

the trueness (and safety) of their wheels, but the threshold

for this testing is likely well below X-Games speed. Therefore,

the wheels that wind up on store shelves have probably not

been tested for the required trueness of high speeds.

Aerodynamics

In motorsports, the concept of "downforce" is a critical issue

in determining the traction of the tires on the road. For an

object (or person) traveling in a horizontal fashion,

downforce refers to a component of air flow which directs

pressure (force) downward towards the ground. In Formula-1

racing, the rear wing is adjusted to vary the level of

downforce on the car and tires. Because downforce is largely

related to the velocity of travel, the level of downforce on a

skater is admittedly not equal to that of a speeding car.

However, the issue is probably important enough to consider.

The magnitude of the downforce is primarily dictated by the

shape of the moving object. In the case of the skater, this

refers to body position. Assuming a deeply crouched position

with the head and shoulders slightly lower than the hind end

would serve to increase the downforce on the skater/wheels. In

theory, the greater the difference in height between the

shoulders and hips, the greater the downforce. Failure to

assume this aerodynamic downforce position may result in the

opposite (and undesirable) effect. Exposing a large portion of

the trunk/chest to air with an open body position (shoulders

higher than hips) would serve to reduce downforce and increase

the resistance to forward velocity. Try to avoid this "parachute"

position and stay low and compact, keeping the head and

shoulders as low as possible.

QUESTION

"Over the past few weeks, I have noticed a significant drop in

my performance. Every time I skate my muscles feel tired and

my leg speed has dropped. Any idea what could be causing this?"

ANSWER

There are several things that could be going on, either alone

or in combination:

You are not eating enough (i.e. inadequate caloric intake) or

you may not be eating the right combination of foods.

Our bodies are machines that require the right mixture of

protein, carbohydrates, essential fats, vitamins and minerals.

Athletes often need to fine-tune normal nutritional guidelines

in order to ensure that they are getting enough of the

nutrients they need most (carbos - fuel, and protein - muscle

repair/maintenance). Feeling tired, weak, or sluggish can be

caused by inadequate caloric intake (not enough carbos) or a

variety of other nutritional deficiencies. For more detailed

information on nutritional issues for athletes, I recommend

Nancy Clark's "Sports Nutrition Guidebook". Check your local

book store or call Human Kinetics (800) 747-4457.

You are ill/injured.

Believe it or not, sometimes we are ill but don't know it. A "silent"

illness, such as a systemic infection or blood disorder (low

hematocrit/red blood cell count), may manifest itself without

any obvious symptoms. Visit your doctor and get your body (and

blood) checked.

You are suffering from cumulative over-reaching or over-training.

Training too much, too often, too intensely, or a combination

of these can lead to a condition referred to as over-reaching.

A mild state of over-training, over-reaching can actually be a

desirable outcome of training because the body grows stronger

once it has had sufficient time to recover. However, if the

early signs of over-reaching (high resting heart rate, muscle

fatigue, disruption of sleep, slower than normal recovery) are

not detected and adequate rest is not taken, the athlete then

enters into the chronic state of over-training. Once over-trained,

an athlete must give the body a considerable amount of time

(2-10 days) to recover fully. If this rest is not taken, the

problem only worsens, necessitating even longer recovery. Be

wary of the warning signs, and be sure to always take

sufficient rest between intense workouts. If you suspect over-training,

take 3-5 full days rest and see how you feel afterward.

Research seems to indicate that no significant de-training

occurs for about 5 days so don't feel guilty about the time

off. Rest does the body good.

To avoid serious over-reaching or over-training, follow these

guidelines:

To allow for the repletion of the fuel source glycogen, allow

a minimum of 48 hours between intense workouts.

Always ensure that you employ a gradual progression in both

training volume and intensity.

Monitor (morning) resting heart rate: 5-10 beats over normal -

train at low or moderate intensity. More than 10 beats higher

than normal - take the day off. Check HR the next day.

If you encounter D.O.M.S (delayed-onset muscle soreness),

either rest fully for 1-2 days or train at very low intensity.

Listen to your body - it's smarter than you think. If your

body is tired, give it rest.

QUESTION

"I am looking to replace my indoor bearings. Many guys on my

speed team use Boss Swiss. There is also the Ninja ABEC-7, but

they cost more. Any insight would be most appreciated."

ANSWER

I can't tell you which bearing is better, but I can tell you

to be wary of claims that higher ABEC ratings equal more speed

or greater efficiency. Once a bearing gets on the ABEC scale,

the discriminating factor is its tolerance (how tightly the

balls fit inside the raceway). In theory, the tighter the

better because there would be less wasted energy. However,

because inline skating places angular loads on a bearing, and

because skate bearings get quite dirty, there is some debate

over whether or not a tightly packed bearing is actually

beneficial. Certainly the ABEC-7 bearing you speak of may be

better. But be careful of how you interpret claims such as "lower

coefficient of friction". This data may come from tests which

don't accurately reflect the way a dirty bearing is stressed

during actual skating.

QUESTION

"I'm in a 5 wheel skate but it has the bulkier ski-type boot.

I feel I have out-grown this skate and am wondering what would

be a good skate to go into. What skate could you recommend

that would be appropriate for my level?"

ANSWER

A lot of people making the transition from a molded boot to a

true speed boot feel overwhelmed by the growing number of

choices. Keep in mind that no matter what you hear from other

skaters, store clerks, etc., the most important things to

consider are price point, functionality and fit.

Functionality

Quite simply, this means finding a boot that suits your needs

(and to some extent, ability). Is all your skating outdoors?

Will you be doing any indoor (inline) or ice skating on the

boot? If not right now, is it possible you may want to do so

in the future? These are all things you have to consider now

to avoid buying a boot that does not meet your current and

future needs.

If you are going to skate indoors (ice or inline) you will

want to find a boot which comes up high enough to fully

enclose the ankle bone. Although this restricts the ankle

joint somewhat, it will give you the support you need for

making tight turns. Most speed boots are designed this way, so

this gives you access to all the major brands...Miller, Bont,

Harper, Simmons, Verducci.

If you are skating outdoors, I strongly advocate a boot with a

lower ankle height (one that comes up just below the ankle, or

close to the top of the ankle . This is where your ability (and

past experience) will come into play somewhat. The less

support you have, the more you have to be technically

proficient, especially when tired such as the end of a race.

In my opinion, this is actually desirable because it is good

to get into the habit of maintaining efficient form during

times of fatigue. High boots permit sloppiness while lower

boots require a little more technical prowess. You have to be

able to judge yourself in this regard and try and decide which

is right for you. A growing number of manufacturers now offer

boots which are slightly lower in height (Miller Criterium

model, Rollerblade Equipe, Simmons).

Fit

For expert advice on boot fit for Bont boots, check out Bont

Fit

Ultimately you have to pick a boot which fits your foot

properly. Don't get persuaded to buy anything other than the

boot which feels the best on your foot (keep your eyes shut

while trying them on). Happy skaters are usually adamant in

their opinion of which boot is the best. Sure, follow their

advice if you like, but you will pay the price later if you

buy a boot that is not right for your foot. It's best to find

a shop that carries several models. But, if there's nothing

near where you live, call each manufacturer to find out how

their boot is made (e.g. wide, narrow, square vs. tapered toe

area, flat arch, etc.). (Use the Advertisers Index in FaSST as

a guide). These are all important considerations, so take the

time to analyze your feet and shop around. Don't be one of the

many who go through 2-3 pairs of boots the first year because

they bought the "in" boot. This is an expensive mistake.

There's no cut and dried recommendation I can give you. Do

some research, talk to knowledgeable skaters (but follow their

"advice" sparingly), speak to the boot makers, know your feet,

then buy the best fitting boot which suits your budget. Your

feet will thank you.

QUESTION

"Can you tell me the best way to position a speed frame on a

boot"

ANSWER

In regard to frame positioning. I have attached a segment from

the upcoming FaSST buyers guide. I hope it helps:

Mounting a Speed Frame

Five-wheel frames attach to a speed boot in one of two ways.

The first and most common method of attachment is to insert a

bolt through the a slot in the frame, and thread it tightly

into the aluminum heel blocks embedded into the front and back

of the boot. Therefore, there is one bolt for the front, and

one for the heel. Most boots have two or three mounting holes

in the front and two in the back. Which one you use will

depend on how you want your frames positioned laterally.

Front to Back Frame Positioning

Most speed frames have two or three lateral mounting slots

which you can use to attach the frame to the boot. When

deciding on which to use, keep this in mind: the goal is

achieve a 50/50 overlap in the front and back of the boot.

That is, when the wheels are on and the skate is viewed from

above, there should be a similar amount of wheel showing in

front compared to the back.

Lateral Frame Position

There is no single answer how to set the lateral adjustment of

a frame. Anatomy, skating technique, and personal preference

all play an important role in finding the right positioning

for you. What follows are general guidelines.

When viewed from above, align the center of the front wheel in

a position between the big toe and second toe. Then look at

the boot from behind and align the center of the rear wheel

just inside of the middle of the boot. Once this is done,

place you hands flat along the sides of the boot and hold the

skate directly out in front of you (as if you were above the

boot). Your hands will be parallel and completely vertical.

Using them as a gauge, what you should observe is that the

skate frame has a slight inwards angle. That is, the toe of

the frame should be positioned slightly more inside than the

heel.

Test Your Mounting

The final step is to put the skates on and stand on them. Make

sure the skates are about 18' apart, and be sure to have equal

weight on both skates. You should feel like you are positioned

directly on top of the highest point of the wheels, or you

should feel a slight inclination to roll each skate to the

outside. If this is not the case (i.e. your ankles want to

collapse inwards), move the frame slightly inwards. Make small

adjustments until you feel right, and then try skating.

Late Update

Received Friday, June 5, 1998 - via

From: BRobexxxxx@aol.com (xxxxx substituted for actual name to

preserve privacy)

I read the article on positioning of the frame on the boot.

But, my question is do you position the frame differently for

indoor speed skating vs outdoor speed skating? If so, what is

the correct positioning for indoor skating?

ANSWER

Whether you position the frame differently between indoor and

outdor depends primarily on how you set it for outdoor. If you

have the frame relatively center set with little or no inward

angle, you probably won't need to change it for indoor.

However, if you have the frame on the extreme inside of the

boot and/or a large inward angle, you will most certainly need

to change it. Not only will the boot hit when the frame is far

inward, but the turned-in angle of the frame will actually

work against you in the turn (i.e., it will make the left

skate track away from the center of the turn when what you

want is to have the frame either straight or turned inwards

towards the turn center). Frame positioning is so individually

specific that its difficult to ascribe guidelines. Sometimes,

you just have to experiment to see what feels right. Keep your

eye on future issues of FaSST. So many people ask this

question that I think it deserves more attention.

Good luck

- Barry

January, 1999

With Barry Publow

QUESTION

When skating, after only

a mile the muscles surrounding my shins become extremely tired,

so much so that after another mile I couldn't even stand up

strait, and my skates would flop left to right. I felt

dangerous, out of control, and worse of all, I physically

could not continue skating!

ANSWER

What you are

experiencing is quite common, and can usually be rectified by

a change in frame position (see the FaSST Buyer's Guide

details on how to set up your frame). Positioning the frame so

that the imaginary line between the front and back wheel lies

too far inside the foot's balance point can put undue stress

on the muscles at the front and side of the shin. Since these

muscles control ankle movement (and therefore affect it's

stability), even small adjustments in lateral frame position

can have a dramatic effect. Most often, shin pain/discomfort

can be alleviated by moving the frame slightly to the outside

(of the foot) in a more "center-set" position. Move both the

front and back about one millimeter at a time until you feel

only a slight tendency to roll the ankle to the outside. Try

skating, and make further adjustments as warranted.

QUESTION

"Whenever I train or

race I always get a very painful stitch. Could you please tell

me how to get over it, or what I'm doing wrong".

ANSWER

Sport scientists are

still somewhat mystified when it comes to explaining the "side

stitch". What makes it difficult is that there is so much

variation. Most researchers who have studied this type of

cramping believe that the pain emanates from a muscle or set

of muscles in the abdomen. Many such scientists believe the

cause to be a spasm in the diaphragm - a somewhat small muscle

separating the chest and abdominal cavities, and one that is

critical for assisting respiration (breathing). Some

researchers believe that a side stitch on the right side of

the body is the result of such a diaphragm spasm, while a

stitch located centrally or to the left is believed to have a

different cause. There is also some evidence that side cramps

can be brought on by dehydration, nutritional deficiencies, or

prolonged exposure to extreme heat. In any case, however, side

stitches seem most clearly related to the breathing process.

Researchers in sports medicine have focused on two primary

methods to quickly get rid of the right-sided type of side

stitch: (1) Breathing Technique, and (2) Posture.

Breathing Technique

If the side stitch is

caused by a muscle problem related to rapid breathing, then

changes in breathing methods can often help get rid of the

side ache. Some researchers have found that shallow breathers

have more problems with side pain than deep breathers. The

next time you get a side stitch, try slowing down and taking

in some really deep breaths. This technique alone will often

bring some relief. As you pick up the pace again, add a very

deep breath every so often. Experiment, and try several

different "rhythms" of breathing. Watch for any method that,

after a while, seems to relieve the pain.

Posture

There is a mistaken

belief that the side stitch is a malady exclusive to running.

In truth, any sport which causes you to breathe hard can

stimulate the onset of such pain. In the case of inline

skating, posture may play a pivotal role in both the

occurrence and treatment of the side stitch. It is likely that

the prolonged "hunched-over" position of the speedskater

interferes with the muscle mechanics of breathing. Try

changing your upper body posture every so often, perhaps even

standing up every few minutes. Since posture changes may be

most beneficial in the treatment of side stitches when

combined with adjustments in breathing techniques, the best

solution is to experiment. This is one area where what works

for one person may not work for another, so take the time to

find the solution that is right for you. Remember the

following guidelines:

-

Strengthen the stomach

(abdominal) muscles.

-

Periodically take

deeper breaths.

-

Stretch the abdominal

area before and after each workout.

-

Avoid eating large

meals or drinking large amounts of liquid before running

hard.

-

Stay hydrated, and eat

a well-balanced diet.

-

Change your trunk

position every so often to alleviate pressure on the

abdominal wall muscles.

QUESTION

What is the best way to

rotate wheels on a 5-wheel frame and how often should I do

this?

ANSWER

If you rotate your

wheels often enough (i.e. every 1-2 weeks) you can just do it

randomly. This is preferable because you will rotate the

wheels before you have had sufficient time to excessively wear

one wheel. If you skate a longer period of time before

rotating, you are almost sure to have worn one wheel (usually

the toe) much more than the others. The idea is to place the

most worn wheel where the least worn is, the least worn where

the most worn is, etc. and rotate each whel 180 degrees. The

secret to wheel rotation is to spend some time looking at your

individual wear patterns. Once you know how your wheels wear,

it's relatively easy to know how to swap them around.

QUESTION

What is the difference

between a "low profile" frame and a "high profile" frame?

ANSWER

It is difficult to precisely quantify the difference between

high and low profile frames because there is no standard which

all manufacturers use. With Mogema, the difference is

approximately 5 mm. What this means is that the low profile

frame brings the boot lower to the ground. Advocates of low-profile

frames point to the lower center of gravity and increased

stability these frames offer. As a result, these are most

often chosen by distance skaters and/or those with low-cut

boots (such as a Viking). For what they give up in stability,

high profile frames offer the benefit of increased pushing

leverage and increased boot clearance on corners. Although

we're only talking about a few millimeters here, the

perceptual and practical difference between these two frame

types is quite remarkable.

Summer 2003 - Vol. 13 No. 2

With Barry Publow

QUESTION

I am new to inline

racing (I have never competed) and am currently polishing up

my technique. I have been told that when I am finishing up a

push stroke, (either forward or crossover) the last wheel to

leave the ground is my front wheel. My coach refers to this

as toeing. I switched to smaller front wheels to solve the

problem of pushing with the toe of the skate, but now I am

confused. All of the images in FaSST show world-class

athletes doing what I am being told is my problem (i.e. the

toe of the push skate is the last to leave the ground).

ANSWER

My

first comment is that caution has to be taken when viewing

still photos. The dynamics of inline technique are such that

a snapshot, or photo, of a skater can often be misleading to

represent technical errors when they do not necessarily

exist. Even a technically proficient skater can look goofy

and awkward in photos. So caution has to be taken when

diagnosing technique using still photography. My

first comment is that caution has to be taken when viewing

still photos. The dynamics of inline technique are such that

a snapshot, or photo, of a skater can often be misleading to

represent technical errors when they do not necessarily

exist. Even a technically proficient skater can look goofy

and awkward in photos. So caution has to be taken when

diagnosing technique using still photography.

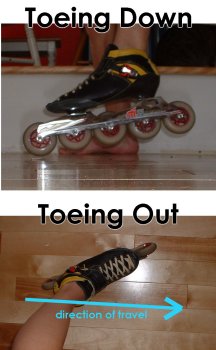

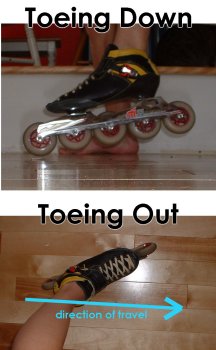

Secondly, lets define

toeing, toeing out or toe flick. There are really two

separate actions, but each is very different. For the sake

of clarity, we will refer to them as toeing out and toeing

down. It is important to realize that the toe (or foot/skate)

can flick either down or out. Toeing out involves erroneous

movement of the entire leg/thigh. The skater will externally

rotate the leg at the end of a stride so that the skate (when

viewed from above) points outwards (from the direction of

travel).

An easy way to

identify toeing out is to look at the direction the knee cap

is pointing. In a skater who toes, out the knee cap will not

be pointing straight ahead, but will instead be directed

outwards. This is a fairly gross biomechanical error, and

reduces the effectiveness of the push. This is seen in

inexperienced skaters and cross-country skiers who

unknowingly rotate the thigh outwards during push-off,

leaving the skate pointing away from the body. The problem

is not that the skate points out, but that power is

compromised because sideways pushing force is reduced when

the thigh is externally rotated at the end of the push.

Toeing down, on the

other hand, involves pointing the toes (flexing the ankle)

slightly at the end of the push so that the first wheel is

the last to leave the ground. If this action is combined

with toeing out, then there are fairly serious limitations

in force output. However, so long as the knee cap is

pointing ahead and the thigh is not rotating externally,

toeing down in itself is not as detrimental to force

production.

The other thing to

keep in mind is how and why the first wheel is the last to

leave the ground. Whenever you analyze a technical

discrepancy, it is important to look a little deeper into

the action and trace the movement back to understand why it

is happening. If the toe wheel is the last to leave the

ground because the skater is actually plantar flexing the

ankle and forcefully pushing the foot/toe of the skate down,

then this is a bad thing. However, if pushing force is

directed through the middle of the foot and the skate/ankle

flops towards the toe at the end of the push then this is

not a big deal. As with all errors, there are varying

extremes, and without seeing you skate it is impossible for

me to conclusively state how much of a problem this is, or

whether you are toeing out or toeing down.

Talk to your coach,

and try to look a little closer at why this is happening.

Are you powerfully pushing the toe into the road, or is the

toe of the skate simply tilting forward at the end of the

push. This is a critical thing to ascertain before

determining the severity of the error, and how to go about

correcting your alignment.

QUESTION

A few days ago, I

started weight training at a local gym. I was doing some

squats and the gym instructor told me that I shouldn't

position my kneecaps past my toes. He told me it would

gradually damage the knee joints and I might develop knee

problems later on. He told me I should position my kneecaps

no further than my toes, or slightly behind the end of my

toes. Does this make sense?

ANSWER

The instructor who

said this you is not totally right but not completely wrong.

It is true that the deeper you squat the more stress is

placed on the quadriceps tendon that inserts onto the

patella (knee cap). When squatting deeply, the tendon is in

a very awkward position to leverage force. This places

additional stress on the knee joint itself and has the

potential to damage cartilage or (more likely) result in a

strained tendon. But this does not mean that you shouldn't

squat fairly low, only that you should be very cautious

about the amount of weight you are lifting. The risk of

injury or damage to the tendon/knee joint increases the more

stress you place on it, however it is important to simulate

the knee angle observed during actual skating.

Posture, technique,

and body positioning is critical if you are to reap the most

benefit from any strength training exercise, and squats are

no exception. In long distance skating, knee angles are

around 110-120°, while sprinters squat even lower (90-100°).

In order to transfer strength gains achieved in the gym to

sport-specific performance, it is important to simulate the

same range of motion when training in the gym. And this

includes developing strength and power at the lower knee

angles.

If you are training

for gains in muscle size and raw strength/power, you are

likely lifting very heavy loads. If this is the case, be

cautious about how low you squat. 110° is deep enough, and

this should place the knees directly almost over the toes.

If you are training for more endurance-based improvements (using

higher reps) it is relatively safe to squat fairly low. say,

90°. Just be aware that the risk of both acute injury a

repetitive-strain/overuse injuries increases when you squat

low, especially when using heavier loads. Use common sense,

and at the first sign of pain or discomfort, either reduce

the amount of weight being used or don't squat as deeply.

QUESTION

I’ve been keeping my

recovery skate as close to the ground as possible. I also

set the skate down a few inches ahead of the support skate.

I discovered I really do not create the conventional D-shape

movement in recovery. It is more like a straight-out then

straight-in movement. I feel good about it and I enjoy the

gliding. Is this a problem or should I consciously make a D

pattern around the back during recovery?

ANSWER

An excellent question,

and one that many skaters have brought up in the past. The

first thing to keep in mind is that classic inline technique

takes its roots from ice speedskating. The problem is that

while similar, ice and inline pose very different frictional

forces to the skater. When comparing the relative duration

of push to glide between ice and inline, its not surprising

that the glide on ice is significantly longer. The bottom

line is that more time is spent bearing weight on the

support/glide leg. In order to prolong glide, minimize

friction, and maintain proper edge control, ice skaters use

a pronounced D-shape recovery around the back. This is the

best method for maintaining stability, preparing for the

subsequent weight transfer, and enhancing the glide phase.

On inlines, the glide

is much shorter, mainly due to higher frictional forces

between the asphalt and wheels. The dynamics of balance

differ greatly because of the elliptical shape of the wheels.

The weight transfer is less dynamic, and a number of

biomechanical elements differ. Hence the D-shape recovery of

ice skating does little to truly benefit the mechanics of

inline skating. In fact, because of the higher stride

frequency of inline, there is some benefit to making the

recovery more efficient, typically by bringing the recovery

skate directly back towards the support leg instead of 'around

the back'. The D recovery of ice technique may be more

aesthetically pleasing, but it does little to enhance the

efficiency of technique on wheels.

Even if you are not

double-pushing, the snap technique is equally effective for

regrouping the push leg and preparing for the weight

transfer. Since D-shape recovery does little to foster

efficiency, logically snap technique is more efficient and

adds the benefit of facilitating a higher stride frequency.

On inlines, recovery is one of the technical elements of the

movement that you can add your own flair or signature to. If

it feels natural, I say keep on truckin'!

QUESTION

I’m going to skate the

Empire Speed 26-mile Marathon, and am fairly new to the

sport. What should my training regimen be? Should I do 12-18

miles a day? Work hills some days only? How often should I

train? I’d like to definitely finish the race and possibly

not last and dying of exhaustion. I’m in good shape, so I’m

willing to put the pedal to the metal…I just have to know

how to go about it.

ANSWER

It’s difficult to

prescribe detailed training recommendations here, but I can

give you some solid general guidelines in terms of training

variables.

-

Frequency - You can skate up to

6 days a week but no more. Your body requires at least 1 day

of full rest, sometimes even 2.

-

Intensity - Keep the intensity

of your long workouts at roughly 65-75% effort. For a long

race your primary objective is to build muscular endurance,

and not necessarily speed. You should feel comfortable, and

be working only moderately hard.

-

Time / Volume - When it comes to preparing for endurance

events (over 90 minutes), the important training variable is

volume. The key is progression! You need to gradually

increase your daily/weekly mileage over 4-6 weeks.

In the beginning your typical daily workout may be 6-10 miles.

But as the weeks go on and endurance improves, you need to

progressively overload your body to ensure continual

improvement. I’d normally advocate a 6-week progression where

you are increasing weekly mileage each week for 3 consecutive

weeks. The 4th week would be a reduced ‘recovery’ week similar

to the 1st. Week 5 would be a higher volume week than 4.

During this week you should have at least one skate that is

roughly 90% of the race distance. Follow this step-like

progression and give yourself a good 5-7 days to peak, taper

and recover prior to the big day.

Winter 2003

- Vol. 12 No. 6

QUESTION

A big deal has been

made about inline clap frames, but in photos I see everyone

on regular frames. What’s the deal? Are they really used for

training or racing?

ANSWER

Clap frames are used

for training and racing. Like most equipment, personal

preferences dictate what an athletes uses. Many immediately

took to claps, while others didn’t. Some felt the benefits

of claps meshed well with their technique, while others

found it a hindrance.

Any new technology

that hits the skating market garnishes a great deal of

attention at first. Some stand the test of time, while

others vanish into obscurity or are eclipsed by the new

latest and greatest. Ice claps are here to stay, but there

remains a great deal of uncertainly about today’s generation

of clap technology. There are die-hard lovers of claps who

would sooner die than give them up. Mogema’s 5-wheel, 84mm

system is currently the latest introduction into the inline

techno war, and this has probably reduced the amount of

attention that clap frames were receiving.

As far as photos go,

it is often very difficult to determine whether or not an

athlete is riding on a clap or a fixed frame. Claps only

reveal themselves during the last part of push-off, and most

photos fail to capture this moment in time. Just be careful

before you conclude someone is on a fixed frame. There may

be a clap frame ready to snap into action a fraction of a

second later.

QUESTION

What test can I

perform to determine how much fast or slow-twitch fibres I

have in my legs?

ANSWER

Unfortunately

there is no easy test to determine muscle fibre composition.

To accurately calculate the ratio of fast to slow twitch

fibres, a muscle biopsy has to be performed. A small

incision is made in the vastus lateralis muscle (outermost

quadricep). A small needle is inserted into the belly of the

muscle (don’t worry, a local anesthetic is used). The needle

removes a small piece of muscle tissue which is then

‘stained’ with a special enzymatic dye. The stain

selectively changes the color of certain muscle fibres, and

the sample is viewed under a microscope. Cells are counted

to determine the ratio of muscle fibres. Unfortunately

there is no easy test to determine muscle fibre composition.

To accurately calculate the ratio of fast to slow twitch

fibres, a muscle biopsy has to be performed. A small

incision is made in the vastus lateralis muscle (outermost

quadricep). A small needle is inserted into the belly of the

muscle (don’t worry, a local anesthetic is used). The needle

removes a small piece of muscle tissue which is then

‘stained’ with a special enzymatic dye. The stain

selectively changes the color of certain muscle fibres, and

the sample is viewed under a microscope. Cells are counted

to determine the ratio of muscle fibres.

This service isn’t

offered just anywhere. You would have to go to a physiology

lab (such as at a university or teaching hospital). It’s a

relatively simple procedure but requires a physician to

perform.

Aside from a muscle

biopsy, there are indirect tests that correlate well with

physical data from a muscle biopsy. Since fast and slow

twitch muscle fibres have different fatigue-resistance

capabilities, the quadricep muscles can be subjected to

repeated cycles of contraction using a fancy machine called

an isokinetic dynomanometer (like a gym machine called a

Cybex or Kinkom that maintains constant resistance

regardless of how much force the individual exerts). But at

$60,000, you’ll only find these at some universities which

have a human performance lab. Call your local university as

quite often graduate students require subjects for both

tests and may be willing to perform such a test either free

or for a small fee.

QUESTION

I’m reading your book

Speed on Skates and in the training section you say that

skaters should skate twice a week during the off-season

phase. My question is, what if I cross-country ski (skate-skiing)

twice a week? Since I’m I using the same muscles should I

still skate twice a week?

ANSWER

There is NO substitute

for skating, but skate skiing is about as close as there is,

especially if you live in cold climates and don’t have

access to indoor facilities. Specificity of training

dictates that muscles must be subjected to the same force,

movement pattern, and contraction speed in order to improve

for a given sport. In this respect, skating has no

substitute. Yet, skate skiing does involve all the prime

mover muscles of speedskating, replicates some measure of

glide (thereby maintaining isometric stretch) and involves a

similar multi-joint action of knee extension, hip extension

and abduction of the leg. For cross training, skate skiing

is top notch.

QUESTION

For my legs, should I

not lift weights at all, in order to maximize my time inline

skating? And if I do decide to work out my legs (in the gym),

how long should I wait before I can strap on the skates

again.

ANSWER

Conventional strength

training is a good way to increase strength and power in

skating muscles. But even when using the most specific free

weight exercises, it is challenging to have the gain

translate into improved performance on wheels.

Strength training

serves its most useful purpose as an off-season and early

pre-season training method when incorporated as part of a

sound annual training plan. Gains in muscular strength and

power can be transformed into sport-specific improvements

when structured in the proper manner, which typically

involved plyometric exercises. While there is no substitute

for time spent on your skates, strength training offers

variable benefits for athletes. Some skaters just can’t seem

to develop the necessary strength from skating alone so

strength training may be the answer. Other skaters have

plenty of natural strength, and should probably invest their

time with on-skate exercises and intervals that develop

power.

The amount of time you

wait before the end of a strength training session and the

next skating session will vary depending on how you are

training with weight and what type of skating you are doing.

But generally speaking, you can probably skate the day after

or even the same day so long as you’re skating easy and not

lifting heavy weight. If you’re lifting heavy loads with low

repetitions, give yourself 24-48 hours before you skate. If

your legs feel ‘dead’, take it easy or wait another day to

allow for complete recovery and muscle repair.

QUESTION

I do a lot of inline

speedskating, but little training for my calves. I mountain

bike 2-3 days a week, but it doesn’t help the fact that

every time I play tennis I will pull/strain my right calf.

It’s not just sore, but really strained. The pull occurs

when I sprint for a ball. My friends are always surprised

because my legs look strong from skating, and feel strong

until this happens. I even try warming it up, and stretching

prior to play. Is this a common problem for skaters, and is

there an ideal way to strengthen or prepare myself to avoid

this?

ANSWER

There are two

important things to consider here. For starters, the way the

calf muscles are used in speedskating (unless you are using

claps) is very different from the way you would use them for

running (or tennis). Calf muscles are involved in static

contraction for maintaining balance and stability during the

glide phase, and contract through a very short range of

motion when you push. By comparison, a running motion places

entirely different stresses on the calf muscles, i.e. they

are forced to contract through a much broader range, and

will shorten/lengthen to a higher degree. Hence your calves

may be very strong for skating, but not strong enough for

other sports. Cycling does involve a higher range of ankle

motion than skating, yet it is non-weight bearing, and

therefore does not impose the same degree of overload.

The second thing is

injury, namely acute tendonitis. The sheath around the

Achilles tendon can easily become swollen, irritated, and

inflamed from skating (especially if your boots don’t fit

well). Even a minor injury can be aggravated once the muscle

and tendon is used in an activity that involved different

stresses. Achilles tendonitis takes a long time to heal and

recover, and can easily be re-injured. Ice the area after

skating or other robust activity, and check with a

physiotherapy clinic for assessment.

QUESTION

I’ll be purchasing

inline speed boots and need help with sizing. I know I

shouldn't be swimming in the next pair of boots, but should

they be a half size bigger to accommodate for foot swell?

Should the extra room be made up by wearing a second pair of

socks? Can you also offer suggestions for arch support

inserts?

ANSWER

All skaters seem to

have their preferred fit, but the boot should be as snug as

possible without causing pain, restrictions in blood flow,

or limitations in range of mobility. Comfort is critical,

but so is the right fit. You are correct that feet often

swell in summer heat, but most boots will stretch anywhere

from 1-3%. This is probably enough to accommodate for foot

swell, so you should fit the boot snugly when it is new.

Having a half-inch of room at the toe is fine if it feels

good and it doesn't cause your heel to lift or your foot to

slide forward in the boot.

In my experience,

wearing a second pair of socks is not a good idea. Cotton

socks hold too much moisture, and two nylon socks will slip

freely past each other causing blisters, heat buildup, and

irritation.

As for orthotics or

other similar inserts, it is better to find a boot that

accommodates the anatomy of your foot rather than try to

correct a poor fitting boot this way. I know skaters who

have put small orthotics in their boots with no adverse

effects. So long as the orthotics are low in profile and do

not affect the fit of the boot (by raising the ankle bone

too high) you are probably fine doing so. Don't assume that

you need them in your skates because you need them in your

shoes. The heel-strike, heel-toe roll, and force mechanics

of running don't exist in skating. Skating does place unique

stresses on your feet, but I’d recommend you consult a

podiatrist or similar expert before you jam orthotics in

your skates.

Summer 2002

- Vol. 12 No. 4

With Barry Publow

QUESTION

Do in-line skaters get

the same intense gluteal muscle build-up that I see in ice

speed skaters? Is there a certain technique to enhance this

build-up or will it come naturally with consistent, low

speed in-line skating?

ANSWER

Other than the 5K (3K

for women) and 10K (5K for women), most metric long track

ice speedskating events are sprint-oriented, and rely

heavily on high levels of absolute strength, explosive power,

and leg speed. As such, ice speedskaters employ training

methods (both on and off ice), which encourage improvement

in these attributes.

Strength trainers and

exercise scientists have known for many decades that the

adaptive response of a muscle occurs in direct response to

the stimulus placed on it. A muscle which is subjected to

high loads and relatively low repetitions responds by

growing strong and larger (hypertrophy). On the other hand,

a muscle which is subjected to many repetitive low-level

contractions realizes an enhancement in the endurance

capabilities of the muscle cells. Ice skaters - at least

sprinters - tend to have highly-developed (i.e. large) leg

muscles (quadriceps, hamstrings, adductors, and gluteals)

because of the way they train, and because of the degree of

stress that racing places on their bodies. Training for

sprint events on the ice will certainly assist in this

muscular growth, but a great deal of this muscular

development can also be attribute to off-ice training (conventional

strength training and plyometric exercises). Besides this

fact, elite ice speedskaters likely have a genetic

predisposition to having “big legs”. In other words, young

speedskaters with the sprinter’s physique are likely

channeled into the sprint program as opposed to being

developed as distance skaters.

If we look at the

training methods and muscular requirements of an inline

racer, the observations are markedly different. Most inline

races are 10K or longer, and rely heavily on strength but

also on muscular endurance. Since there is little or no

performance correlation between high relative muscular

endurance and muscle size, inline success does not depend so

heavily on having such well-developed thigh muscles. The

inline sprint specialists tend to be more heavily muscled in

the lower body, but even some of the fleetest feet in the

business are attached to surprisingly lean legs.

QUESTION

I will be purchasing a

pair of inline speed boots and need assistance with sizing.

I know I shouldn't be swimming in the next pair of boots I

buy, but should the boots be a half size bigger to

accommodate for foot swell? Should the extra room be made up

by a second pair of socks? Any suggestions for arch support

inserts?

ANSWER

All skaters seem to

have their preferred fit, but generally speaking the boot

should be a snug as possible without causing pain,

restrictions in blood flow, or limitations in range of

mobility. Comfort is critical, but so also is the right fit.

You are correct that feet often swell in summer heat, but

most boots will stretch anywhere from 1-3%. This is probably

enough to accommodate for foot swell, so you should fit the

boot snugly when it is new. Having a half-inch of room at

the toe is fine if it feels good and it doesn't cause your

heel to lift or your foot to slide forward in the boot.

In my experience,

wearing a second pair of socks is not a good idea. Cotton

socks hold too much moisture, and two nylon socks will slip

freely past each other causing blisters, heat buildup, and

irritation.

As for orthotics or

other similar inserts, it is better to find a boot that

accommodates the anatomy of your foot rather than try to

correct a poor fitting boot this way. I do know skaters who

have put small orthotics in their boots with no adverse

effects. So long as the orthotics are low in profile and do

not affect the fit of the boot (by raising the ankle bone

too high) you are probably fine doing so. Just don't assume

that you need them in your skates just because you may need

them in your shoes. The heel-strike, heel-toe roll, and

force mechanics of running don't exist in skating. Skating

does place unique stresses on your feet, but I would

recommend you consult a podiatrist or similar expert before

you jam your orthotics in your skates.

QUESTION

My 17 year-old is

having trouble with his leg muscle locking up during short

indoor races. He has been on a training program for a year

and is in great racing condition. He also trains with a

trainer for outdoors and does quite well. Even with

stretching and a warm up, his legs go dead at 1000m. This is

something new and causes him to slow up even though his is

not winded. After several races he feels great and again can

sprint. It seems too short for a lactic acid build up.

ANSWER

First off, lactic acid

production begins just seconds into a high intensity race

such as the 1000, and can reach troublesome levels in about

15 seconds. When blood lactate levels reach high levels, the

substance interferes with the contractile mechanics of the

muscles, impairs coordination, and leads to early fatigue.

It is quite possible to experience the ‘burn’ of lactic acid

without feeling ‘winded’ as you speak because lactic acid is

a product of anaerobic energy metabolism.

In addition to the

above, there are several other possible causes/factors. The

first is a lack of proper warm-up and activation of aerobic

processes. A skater who goes to the line of a 1000m race

without a good 10-15 minute warm-up is just asking for

trouble. Some skaters think a 2-minute jog around the rink

or a few easy laps will suffice. The second, possible cause

is overtraining and/or fatigue. A skater who is not well-rested

and tries to race on tired legs will feel exactly like you

have described. Many skaters are chronically overtrained and

don’t even know it. Rest, recovery, and a review of past few

months of training can be helpful in diagnosing a skater who

is overtrained. It may also be useful to monitor morning

resting heart rate over the long term as an early indicator

of fatigue. And a last point I should mention…having one’s

legs go ‘dead’ during an intense race is quite normal and

par for the course. Anyone who finishes a race and still

feels springy probably didn’t skate hard enough (or is named

Chad Hedrick).

QUESTION

For this, assume all

things are equal. If an inline speed skater races a 500m

race on a short track layout and records the time then tries

the same 500m in a straight race - no turns - which time

will be faster? My workout partner maintains that the short

track time is much faster…that turns somehow generate

additional speed. I disagree, and believe that the straight

500 time would be faster and is much more energy efficient

over the course of the distance than including turns. Who's

right Barry?

ANSWER

Interesting question.

The answer is that you are both right in some respect. Your

friend is correct that you can generate speed on a turn

using crossover steps and exit the corner at a higher

velocity. But you are correct that a straight line 500

sprint would be faster than a 500 indoor time. There are

several reasons:To roughly calculate caloric expenditure you

need 3 pieces of info:

-

There is limited

traction when skating indoors (even on the grippiest floor),

making it impossible to hold a tight line and avoid

slipping at high speed. Outdoors, a world-class sprinter

can reach speeds of 50kph+. I don’t think there is skater

in the world who can hold a nice, clean line (and still

crossover) at this speed. In fact, it would be impossible

for an indoor skater to even accelerate up to this speed

in the first place.

-

The tight corner

radius of indoor skating is not conducive for generating

maximum radial velocity while at high speed. This is why

many skaters are forced to coast a portion of the corner

when going fast.

-

As mentioned, the

straightaway distance in indoor skating is not long enough

to reach maximum speed to begin with.

If you want actual

related proof, just compare banked track versus road times

for 300m and 500m at the World Championships. Road times (which

typically have longer straights and ‘wider’ corners) for the

300 and 500 distances are usually 2-3 seconds faster. And

since banked track is ‘faster’ than indoor, it would be

logical to assume that road is faster than indoor.

Now, to introduce an

intriguing element to your question…what would be faster…a

straight line flat 500 sprint or a 500 sprint on a track

with straights and corners designed to optimize speed. In

such a case, I believe the track would be faster!

QUESTION

I recently started

inline speedskating after converting from rec skates and

I've been in training with a local team for over a month. I

haven't seen an increase in my endurance after all these

times. Is there some sort of exercise to increase endurance

so I do not get tired after 5-10 laps?

ANSWER

Training for the sport

of inline racing requires attention to both the aerobic and

anaerobic energy systems. Aerobic energy metabolism requires

plenty of oxygen and carbohydrate/fat for fuel source.

Intensity must be low to moderate so that lactic acid does

not accumulate in the muscles and in the bloodstream.

Anaerobic conditioning, on the other hand, does not require

oxygen to break down glycogen, and characterized by high

intensity effort and a rapid build-up of leg-burning lactate.

It is difficult to

provide you with specific advice without knowing more

details such as how fast you are skating these 5-10 laps. If

you are skating a 1000m race and are zonking after 6-7, then

the issue is one of anaerobic conditioning. If you are

skating 25 moderately-intense steady laps and are tiring

after the same number, then the issue is likely once of

aerobic power output and muscular endurance. If you’re

training with a club, then you likely have a coach. Talk to

your coach to try get to the bottom of the ‘weakness’ you

are referring to, and then address the issue by employing

training methods that focus on the attributes in question.

If you want more detained information on training the

various energy system components, read Speed on Skates,

published by Human Kinetics, or the online articles at

www.breakawayskate.com.

QUESTION

I just converted from

rec skates to 5-wheel speed skates. This is my 6th week on

these skates and I've been having problems with it. For

starters, both of my shins hurt after only a few minutes of

skating. And not only that, but almost all the time my right

foot gets numb after 5-10 minutes of skating. What is

happening to my feet? This never happened before.

ANSWER

For starters, your

shin pain/fatigue is quite normal and should dissipate over

time. If not, then it’s time to check frame alignment and

make adjustments (check out the Ask the Expert archive at

www.breakawayskate.com). Even minute fine-tuning can have a

huge impact because it alters the balance point of your foot/ankle

and can reduce the static stress experienced by lower leg

muscles which are struggling to maintain stability during

skating.

As for the foot

numbness, try loosening your laces, use an alternative

lacing method, stretch pressure points, and maybe even mold

your boots (if they are heat moldable). Sometimes there is a

break-in period for your feet as well as your boots, but 6

weeks should be enough time to achieve a reasonable comfort

level. If the problem still persists, the cause is likely a

poor fitting boot that is too narrow and not shaped right

for your anatomy.

June 2002 -

Vol. 12 No. 3

QUESTION

I am a 35 year old

male, and have been involved in some form of sports for most

of my life. For a very long time I have been fascinated with

the sport of speed skating. Can you give some advice on how

to get started and what good books might be out there that

can give me solid advice on training?

ANSWER

I am unsure whether

you are talking about ice or inline speedskating, but I

suppose my advice would be somewhat the same. If you are

interested in inline speed, call your national sport

organization (USA Roller Sports in the United States, Roller

Sports Canada in the great white North). They can refer you

to a club nearby, and point you in the right direction.

Next, decide on your

level of commitment and how much you want to invest in

equipment. Try to focus on your long-term goals so that you

don't have to upgrade in a month or two. If you are really

serious, I suggest you get yourself a good pair of boots

right away. Talk to manufacturers, find a reputable shop

with knowledgeable staff and get your gear. Learn as much as

you can about training, find a few local events, and off you

go. May I suggest "Speed on Skates", by Barry Publow (me),

or if you want general training information there are many

good books which discuss basic elements of endurance sport.

Check out Human

Kinetics.

QUESTION

When is the anaerobic

alactic system relied upon in a skating race?

ANSWER

The anaerobic alactic

system is the most powerful but short-lived of the body's

three (3) energy systems. Like the anaerobic lactic system,

the chemical reactions take place without the need for

oxygen. However, because this energy pathway uses phosphate-bound

molecules instead of glycogen for fuel, lactic acid is NOT

produced. This channel, also known as the ATP (adenosine

triphosphate) – CP (creatine phosphate) system, runs out of

fuel and cuts out after roughly 6-8 seconds of all-out

effort.

The ATP-CP system is

unquestionably important for the first 6-8 seconds of a

standing start sprint. It may also come into play during an

intense breakaway or the final sprint down the home stretch.

But since it has a very limited capacity, its contribution

towards success in prolonged events is questionable. The

system needs plenty of oxygen and low intensity exercise or

rest to recharge fully. This means that other than the start,

this energy channel does not contribute much towards overall

energy production. The anaerobic lactic system (the one

which breaks down glycogen without oxygen to produce lactic

acid) is the energy pathway which is far more important to

the speedskater (except for perhaps short sprints such as

the 300m).

QUESTION

I started skate-racing

recently and am 35 years old. I would like to know about the

age required for skate racing competitions.

ANSWER

There is no official

age limit in this sport. Most competitions divide

competitors up based on age or ability. Outdoor events are

typically mass start where everyone starts together and

results are done by age / division. In some larger races

there will be a separate competition for novice, advanced,

pro, etc.

QUESTION

I'm 39, weigh 225

pounds and stand 5' 11" (178 cm). Can you tell me how many

calories I could expect to burn in a 45 minute skate? I keep

about a 6 minute per mile pace

ANSWER

To roughly calculate

caloric expenditure you need 3 pieces of info:

-

Your body weight in

kilograms

-

The duration of the

exercise

-

The rate of energy

expenditure (expressed as met's).

A met or metabolic

equivalent, is a way of expressing the rate of energy

expenditure from a given physical activity. 1 met is defined

as the energy expenditure for sitting quietly, which for the

average adult is approximately 1 kilocalorie per kilogram of

body weight per hour burned. In other words, 1 met is equal

to 1 calorie burned per kilogram of body weight per hour. So

if you weigh 60 kilograms, your energy expenditure for

sitting quietly is around 60 calories, meaning you burn 60

calories per hour just from sitting quietly.

To determine the

number of calories you are expending from an activity,

multiply your body weight (in kilograms) by the met value

and the duration of the activity (in hours-take the number

of minutes you exercise and divide by 60).

Example: 225 pounds =

102 kilograms (1 kg = 2.2 lbs); 6 minutes per mile = 10 mph,

which is roughly equivalent to a met level of 6 (met charts

can be found on the web). If you skate 45 minutes you will

have expended the following calories:

6 (mets) x 102 (Kg) x 45/60 (time) = 459 calories

Keep in mind that this is a fairly crude measure. There are

a host of other factors, such as age, body composition,

fitness level and other individual variables, that can

impact the calculation.

Summer 2003 - Vol. 13 No. 2

QUESTION

I would like to know

if you have any suggestions concerning skating on a wet road?

In my last event, the road was wet and people were passing

by me as if I were standing still and when we got to the dry

part, it was me that was passing them.

ANSWER

I am sure there are

many skaters out there who can relate to your frustrating

wet weather experience. There are two main factors that

influence the ability to skate fast on wet roads: wheel

selection and technique.

Wheel Selection

Wheel selection can

have a huge impact on the ability to maintain traction on

slippery asphalt. Unfortunately, there is no magic wheel

that works in all conditions. The best things to do is test

several wheels on race day, but this is often too expensive,

time consuming, and impractical for most skaters. I

typically keep two sets of rain wheels (78A and 81A) with

grease packed bearings and select one of those for rainy

races. Softer wheels often grip better, but not always.

Sometimes the soft wheels slip even more. Having a back-up

set of wheels/bearings is a good idea, and gives you the

option to ditch your hard “dry weather” wheels.

Technique

There are a few minor

technical modifications which you can execute to help

improve traction in sloppy conditions. For starters, “sit”

slightly higher and use a faster stride frequency. Shorter

pushes give you more control when you slip, and allow you to

maintain power output without pushing so hard each stride.

Secondly, try to keep your wheels as vertical as possible as

late into the push as possible. Wheels tend to slip more as

they become more progressively angled near the end of the

push. When combined with a shorter sideward push, these two

modifications can drastically improve traction. And lastly,

try to change the rate of force development in your push.

Normally, a push is “accelerated” and increases in speed and

force the further the skate travels away from the body.

Three quarters of the way through push extension power is at

maximum, and this is typically where slip occurs. Instead,

try to generate more force at the start of the push, and

then “ease off the gas” toward the end. This takes practice,

but also help to facilitate a slip-free extension

QUESTION

Reading Barry Publow’s

book, Speed on Skates, I know that it would certainly be

beneficial to train with the machines and equipment shown in

the chapter: “Building Strength and Muscular Endurance”. Is

it really necessary to go to a fitness studio? At the moment

I cannot afford a membership to a fitness club, but still

would like to benefit from those types of workouts that

involve weights and machines. What types of alternatives can

I use to achieve similar results without the use of

equipment found at a fitness studio?

ANSWER

There are a number of

“home” exercises that can be performed to give you similar

strength/power benefits. These exercises can be divided into

three categories: 1) Plyometrics, 2) Weight bearing

resistance exercises, and 3) Imitations.

- Plyometrics

-

Plyometric exercises

use body weight, the force of gravity, and hops/jumps/bounding

to load the muscles with resistance. Plyometric drills

should be skate-specific, and mimic the specific pattern

of muscular use in speed skating. Skate leaps, leg

switches, tuck jumps, crossover bounding…the list goes on.

There are too many drills to even mention in a short

article like this. Speed on Skates includes a chapter on

plyo training, and there are numerous other books on the

market which describe this form of supplementary strength/power

training. Check out Jumping into Plyometrics by Donald Chu,

or search Amazon.com’s database. Human Kinetics publishers

is also a good starting point (http://www.hkusa.com/).

Weight-bearing resistance

exercises

Weight-bearing

resistance exercises are freestanding, multi-joint

movements which simply use body weight to load the muscles.

You may not be able to load the muscles with as high a

resistance when compared to free weights or “machines”,

but the benefits are similar. Single leg squats, wall sits,

and side lunges are all good examples. Many lower body

free weight exercises can be done without external

resistance, or buy inexpensive 25 pound barbells to add a

touch of stress to an exercise.

Imitations

Imitations are

weight-bearings exercises which allow you to increase

strength by spending time in the “skating position” i.e.

90° knee bend, flexed trunk, etc. Dryland skating is

probably the most common and useful imitation. Low walks,

and uphill crossover steps are also useful. Dryland

skating can be done on the spot or with forward travel.

Add a plyometric (i.e. jumping) element to dryland skating

to create a super plyo/imitation exercise.

With all of these

exercises the principle of progressive overload must be

followed. That is, start off with a small number of

repetitions / sets and gradually increase the intensity and

frequency of exercise as you get stronger. Plyo drills can

induce considerable traumatic stress if you wade into high

intensity exercises right away. Use common sense and start

off small.

QUESTION

I was wondering if you

would be able to tell me the breakdown of the 1500m for

women, on the short and long track…such as: which energy

systems would be used? How much muscle output during the

beginning middle and end of the race? How to prevent

fatigue?

ANSWER

For many reasons, the

1500m is the most difficult metric distance to train for.

This is because the time (2 minutes at the elite level, and

2:30 – 3:00 for competitive skaters) and intensity (85-90%)

involved represents the classic “50/50” split between

aerobic and anaerobic energy contribution. Skaters need good

acceleration and high levels of strength and power, but also

a well-defined aerobic system. Like the 800m on the track (running)

skaters need to split their training to develop both ends of

the spectrum (power vs. endurance).

In long track,

conventional strategy is that athletes should skate near-equal

splits in terms of lap times (3 x laps). This makes sense,

but is difficult to actually perform in the face of

constantly increasing heart rate and lactic acid

accumulation. Because of this, the athlete will perceive the

race to get harder and harder. It takes many years to learn

the art of pacing, and to train the physiologic components

necessary to be a good 1500m specialist. The skater must

start hard, get up to cruising speed as quickly as possible,

and then try to stay relaxed through the first 600-800m. As

1000m approaches, it becomes increasingly difficult to

maintain the desired power output and lap time, so the

skater must consciously exert more effort, while at the same

time trying to maintain technical efficiency. The last

corner is skated at maximum intensity to try and maintain or

elevate finishing-straight speed. Is it no wonder that blood

lactate levels are higher after the 1500m than following any

other metric distance.

The 1500m race on

short track is entirely different. Short track is highly

strategic, and there is a wide range of tactical options.

Often, the first 500-800m is skated at a comfortable pace,

with skaters positioning themselves and feeling each other

out (and trying to determine each other’s strategy). At

about 1000m things usually heat up. Some skaters try to race

from the front for the last few laps, while others are

content to sit in 2nd or 3rd and execute a late pass. And

while this may be the stereotypical race, this is not always

the case. Sometimes a skater decides to shake things up

right from the start and take off. Sometimes no one chases

and they are able to lap the field, other times the others

will give chase and close the gap. The pace may then slow

before picking up again in the last 4-5 laps, or it may

remain high throughout (this is usually how the world record

is broken). Short track skaters need speed, power, and

superior passing ability, especially if they choose to sit

back until the last lap or two. Strong skaters who lack

these attributes usually prefer to race at the front, keep

the pace high, and force others to pass (and make mistakes,

take chances, get DQ’d, etc).

QUESTION

I have extremely

skinny ankles and I cannot find a boot that fits or comes to

being a good fit around my ankle and therefore my boot leans

to the inside. What can I do?

ANSWER

Talk to boot

manufacturers and ask them about fit in the ankle area. Some

companies manufacture a narrow fit boot/model. Otherwise,

spend a little more money and get custom-fitted boots that

are built for your anatomy and skating style.

QUESTION

I met a serious biker

(nice guy too) that shaved his legs. He said it was to

reduce injury during sliding on the asphalt – seem the hairs

really pull out the nerve endings? I have had a few good

slides and they hurt but I have yet to shave my legs. Is

this the reason to shave the legs, or do the ladies just

really like it?

ANSWER

Well, my experience is

that many women like shaved, muscular legs…especially if

they are athletes too. But this is not the reason we (men)

shave their legs (or is it?). Excluding vanity, there are

five justifiable reasons for shaving:

-

Hairy legs under a

skinsuit feels terrible, and the tongue of the boot may

cause irritation on hairy shin bones.

-

If you crash and

have hairy legs, the friction of the road can actually

case more damage to the skin by tearing out hair follicles.

-

Shaved skin is

easier to clean and disinfect after a crash, and you’re

less likely to develop an infection.

-

Bandaging (after a

crash) can be removed from shaved skin without the need to

emit a long series of four-letter words.

-

Massage is easier

and more enjoyable for the giver and receiver.

Contrary to popular

rumor, unless you resemble the Sasquatch, there is no real